CONTENT

City for all, places for all?

Public spaces in cities are meeting places, places of exchange and communal living. But what happens when a growing proportion of the population can no longer use these spaces? People with dementia are often excluded from public spaces – not because they want to be, but because cities are not made for them.

This is a challenge for local authorities, but also an opportunity. Because a dementia-friendly city makes life better for everyone. It shows how societies can combine social participation, orientation and security.

But how do cities and municipalities achieve dementia-friendliness? How does a city become a city for everyone?

Abstract:

How can cities be designed in such a way that they are accessible to everyone – including people with dementia? This challenge is growing with demographic change.

Dominik Lorenz shows why dementia-friendly urban planning is important, what solutions are available and how everyone benefits.

Demographic change – and its effects

With demographic change, the proportion of older people in Germany is growing rapidly. By 2040, almost a third of the population is expected to be 65 or older, and the number of people with dementia is rising accordingly.

What initially appears to be a purely medical or care-related problem has a huge impact on our cities: when people with dementia are torn away from their familiar surroundings – whether due to unclear structures, a lack of orientation aids or a lack of security – they withdraw. They lose their autonomy, their social participation and often also their trust in their own environment.

For local authorities, this not only means higher care costs, but also the loss of a part of their urban society. But this is precisely where an opportunity lies: urban planning that includes people with dementia creates places that are accessible and liveable for everyone.

What makes a public space dementia-friendly?

Accessibility alone is not enough to make public spaces accessible to people with dementia. Rather, fundamental needs must be taken into account – from quality of stay and opportunities for encounters to orientation and safety.

The quality of a square or park determines whether people want to spend time there. For people with dementia:

- inviting seating,

- shady areas and

- calming elements such as green spaces or water are particularly important.

Public spaces with these conditions not only offer relaxation for everyone, but also enable people with dementia to feel safe and secure.

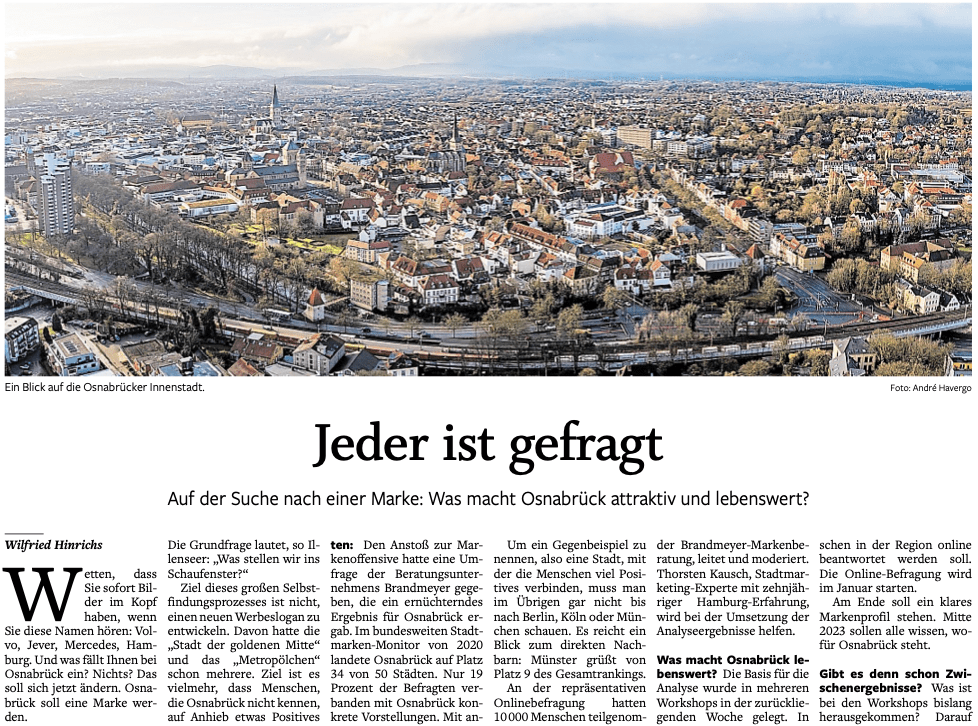

Public spaces are there for everyone – including older people in our society

Encounter, orientation, safety: basic requirements for participation for people with dementia

Encounters are the key to social participation

Public spaces that are deliberately designed as meeting places promote togetherness and prevent isolation. Community gardens, neighborhood centers or well-designed squares are examples of how encounters in public spaces can be actively promoted.

Orientation thanks to clear structures

Orientation also plays a key role: people with dementia often lose the ability to find their way around complex environments. Clear structures, recognizable landmarks and clear signage provide orientation and reduce stress.

Security strengthens independence

Safety is important for every city and for every member of a city: well-lit paths, barrier-free access and quiet retreats make public spaces accessible and trustworthy. Traffic calming can also help to ensure that people can move around safely.

For people with dementia, safety is often a decisive factor in whether or not they can use public spaces. An environment that offers protection and at the same time allows freedom of movement creates confidence and strengthens independence.

Practical example: The Fliedner village in Mühlheim

The Fliedner Village in Mühlheim an der Ruhr (North Rhine-Westphalia) shows how the approaches of a dementia-friendly environment can be implemented: The facility, which is run by the Theodor Fliedner Foundation, is designed like a small town. There is a bakery, a supermarket and normal streets – places that reflect everyday life.

Basic principles of the Fliedner Village: inclusion and freedom of movement

A key principle of the Fliedner Village is the absence of fences or walls, that would restrict or isolate people with dementia. Instead, those affected can move freely and lead a life with as few restrictions as possible. This approach sends a strong signal against deprivation of liberty and shows that people with dementia can also be part of an open and functioning community.

The Fliedner Village pursues a strongly inclusive approach: people with and without disabilities can live together here on an equal footing. The houses are occupied either by people with a disability or a care degree or by people without a disability. The majority of people with a disability are affected by dementia.

This diversity not only promotes inclusion, but also ensures mutual understanding and a respectful community in which every person has their place.

Dementia-friendly Fliedner village: relocation remains a problem

A sensory garden, community gardens and a guidance system with orientation pillars were created especially for people with dementia, making everyday life easier and giving those affected more security.

But there is one decisive limitation: the Fliedner Village was built on a greenfield site and remains a care facility in terms of its basic structure. In order for people to move there, they have to leave their familiar surroundings – a change that can accelerate the course of the illness.

Dementia-free city: making existing neighborhoods inclusive

Instead of creating new facilities, cities should focus on making existing neighborhoods more inclusive. People with dementia should be able to stay in their familiar surroundings for as long as possible. This requires clear orientation aids, safe routes, places of retreat and meeting spaces directly in the residential areas.

These measures not only enable people to remain in their homes, but also strengthen social ties in the neighborhoods.

Inclusive urban planning:

Inclusive urban planning aims to design cities in such a way that they are accessible and usable for all people – regardless of age, gender, disability or social status. Accessibility, social justice and the needs of marginalized groups are integrated into the planning process in order to promote sustainable and equitable urban development.

In terms of dementia-friendliness, inclusive urban planning means making it easier for everyone to live in their own neighborhood instead of moving people to specialized facilities.

Everyone benefits from dementia-friendly spaces

Creating a dementia-friendly city is not a measure that only benefits one specific group. Rather, all city residents and visitors benefit from it – older people, families with children, tourists and the local economy:

- A public space with a high quality of stay becomes a magnet – for weekly markets, walks or cultural events.

- Meeting places strengthen social cohesion and create a positive image of the city.

- Clear orientation aids not only help people with dementia, but also visitors and new residents to find their way around.

- A safe environment invites you to move around freely, whether on foot, by bike or in a wheelchair.

“The benefits for local authorities are obvious: dementia-friendly spaces are an investment in the future. They make the city more attractive, promote social participation and reduce costs in the long term, for example by maintaining the independence and personal responsibility of older people.”

Back to the center of society: Older people also have a right to their place in public spaces

A look into the future of the city: inclusive equals sustainable?

A city that takes people with dementia into account is a city that understands that quality of life must be accessible to all. After all, inclusive urban development is not just about removing barriers, but about creating spaces that offer safety and enable people to come together.

This is a huge responsibility for local authorities – but also an opportunity. By taking measures to make cities more dementia-friendly, they are setting an example: for a city that leaves no one behind and for a future in which quality of life and inclusion go hand in hand.

“Now is the time to seize the opportunities of inclusive urban development. Cities that act today will be more liveable and sustainable tomorrow.”

Image credit: Unsplash.com

Dominik Lorenz

is a project assistant at Stadtmanufaktur. In his master's thesis, he focussed intensively on the topic of ‘Dementia in the city’